|

Shreeya Bhogle

A career in general practice can be like marmite to medical students - they either love it or hate it. However, interestingly, medical graduates from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge have a lower intention to become GPs compared with other UK medical graduates. A 6-year prospective cohort study aims to understand what factors are underlying this, and has yielded some interesting results from its first year. The study involved an online survey of medical students admitted in autumn 2020 to the three East of England medical schools: University of East Anglia (UEA), University of Cambridge (UOC), and Anglia Ruskin University (ARU). It found that UOC students’ lower intention to become a GP appears to be present on entry to medical school, and that this may be explained in part by these students placing a higher importance on research/academic opportunities, combined with the widely held perception that GP careers lack these opportunities. These findings suggest a need to address perceptions of lack of research/academic opportunities in GP careers to raise the profile of academic general practice. This will help guide how we at Cambridge GPSoc plan our upcoming events and lecture/workshop themes for our conference on 5th March 2022. Keep an eye on our social media accounts for more updates! Facebook: www.facebook.com/CambridgeUniGPSoc Instagram: @cambridgegpsoc You can read the paper for yourself here: https://bjgpopen.org/content/5/6/BJGPO.2021.0120

185 Comments

Kalyan Mitra With the start of my first GP placement of 5th year came about a completely new daily routine. Instead of sleeping in and attending my 9am Zoom lectures in my dressing gown, I was up at half 6, and groggily (read: inaccurately) swabbing my tonsils at 7 for the weekly asymptomatic screening, leaving the house just late enough for my gloating housemate to wish me a safe journey as he rubbed the sleep from his eyes (he was placed at a surgery not 5 minutes walk away). After a brief stop at college to deliver said swab, I soon found myself cycling on the B1049 as it meanders northeast of Cambridge, passing first Aldi and Iceland before the more scenic views of the sun rising over the empty fields opened up. 8 miles later and I arrived breathless and sweaty in Cottenham, and by following the high street up a gentle incline I reached the Cottenham Surgery itself. The practice has just one GP partner, and a list size of just under 4,000 patients, making it quite the rarity in an NHS that encourages ever-larger practices in its endless quest for efficiency. From 2013 to 2018, 900 practices closed, and list sizes have risen by almost 20% to 8,279 patients. But are smaller practices actually less efficient, and what is lost when yet another local surgery joins a supergroup? The demise of the small practice is not a new issue, but instead the product of reforms going all the way back to the founding of the NHS in 1948. At that time GP partners remained self-employed, getting paid by the NHS per patient, which remains the case today. Nearly all GPs worked in single-handed practices or with one partner, but working conditions were poor, as were standards of care. Over time, with better contracts and increased professionalisation, practices improved, and with the advent of the ‘red book’ deal, where the NHS pays for 100% of facilities costs and 70% of staff costs, the size and scope of services offered by practices has never been greater.

A quick review of some literature reveals mixed results. On the one hand, in 2016 the CQC found a direct correlation between ratings and practice list size, with the average ‘inadequate’ practice having a list size of 4,755, ‘requires improvement’ 6,311, ‘good’ 7,682 and ‘outstanding’ 9,598. But are the CQCs outcomes biased towards larger practices anyway, requiring a huge amount of administration to meet their targets and therefore favouring practices with less capacity for such paperwork? Independent research has shown minimal effect of practice size on quality, including this systematic review from 2013, and some other papers have even shown benefits to smaller practices, such as lower rates of preventable hospital admissions. In 2016, the Nuffield Trust published this 111 page report, investigating whether bigger really is better. They found that whilst larger practices improved financial sustainability, there was no significant evidence that they outperformed their smaller counterparts. Equally important were concerns raised by patients, who faced a trade-off between better access to healthcare and losing their relationship with their trusted GP.

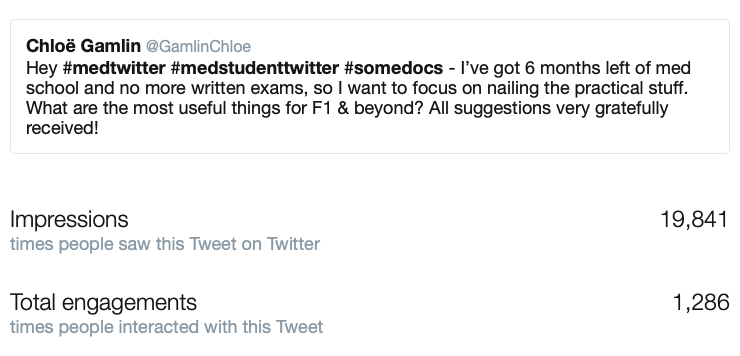

It seems only one thing is certain in this exciting area of public health, and that is that sooner or later the end of the small practice will come. Like the rest of the high street - the greengrocer, the butcher, even the local pub, few independent traders can hold out against the conglomerates for long. One American study observed that physicians in smaller practices were more likely to have been working for more than 30 years, and worked in rural areas, perhaps indicating which practitioners are battling the inevitable. Larger practices will save money in the long-term, and will be able to offer more services for their patients. I’m sure that as we get more experience in operating these bigger institutions, quality of care will increase as well, but something else will be lost, a certain romance epitomised by John Berger in his “Fortunate Man”, of the single GP battling the ills of their community alone. Perhaps it’s not important, but in this increasingly divided, harsh and cruel Britain , the comfort of seeing a local GP is one that will sorely be missed by many. Chloe Gamlin In a burst of nauseating enthusiasm over Christmas, I asked the sizeable corner of the internet that is #MedTwitter for advice on what to focus on for the final six months of medical school to help me prepare for F1. I was incredibly grateful to receive an extraordinary number of responses from doctors across the UK, which I’ve split into several categories below to make for easier reading. Enjoy!

DAILY TASKS Practical Skills Lots of people highlighted these practical skills as particularly useful for FY1:

And others broadened the traditional idea of practical skills to include:

Documentation

Prioritisation and Organisation

WORKING ENVIRONMENT Communication Skills

Relationships

LOOKING AFTER YOURSELF Support from Colleagues

Wellbeing

Maintaining Non-Medical Interests

AND FINALLY… Preparations just before starting F1

Thank you to everyone who contributed to the twitter thread! Chloe Gamlin Dr Kevin Barrett talks about Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD) for Crohn's and Colitis Awareness Week12/7/2019  By Shu Hui Leow It is Crohn’s and Colitis Awareness week! Yesterday, Dr Kevin Barrett delivered an engaging and relevant talk about Irritable Bowel Diseases (IBD) at the Clinical School, offering a unique perspective on IBD as clinician, patient, and champion for better care. The talk was pitched to students in their first and second clinical years, covering history, atypical presentations, diagnosis and management of IBD with humour and candour. Dr Barrett shared his personal experiences living with IBD and his work as IBD champion. He highlighted how IBD impacts every aspect of a person’s life and permeates all areas in medicine, from systemic manifestations to medication and logistical concerns. He also provided insight into how IBD symptoms can interfere with normal day-to-day life, that we as clinicians may not think of, such as requiring easy access to a toilet at work. In addition, Dr Barrett addressed the entrenched belief that smoking protects against Ulcerative Colitis – a recent study1 shows that this oft-quoted relationship has no evidence basis. Many thanks to Dr Barrett for providing his specialist and expert view on IBD! About Dr Kevin Barrett: Dr Barrett is a General Practitioner in Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire and former Clinical Lead for Gastroenterology and Herts Valleys Clinical Commissioning Group (HVCCG). His first medical job was in Gastroenterology and he has maintained an interest in this area since becoming a GP. He is currently clinical champion for the Royal College of GPs and Crohns and Colitis UK’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease spotlight project, as well as Chair for the Primary Care Society of Gastroenterology. He was diagnosed with undeterminable IBD in 2005. This talk was co-hosted by Cambridge University GPs Society and Cambridge University Gastroenterology and Hepatology Society. Huge thanks to Adelaide from Cambridge GPSoc and CU Gastro Soc for making this happen and providing delicious snacks! 1 Blackwell, J., Saxena, S., Alexakis, C., Bottle, A., Cecil, E., Majeed, A., & Pollok, R. C. (2019). The impact of smoking and smoking cessation on disease outcomes in ulcerative colitis: a nationwide population-based study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 50(5), 556–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.15390 By Shu Hui Leow (Current Affairs)

|

|